Last year Ms. Sinclair found herself at Mitsukoshi near school after Tsai Ing-Wen was elected and bought a box of doughnuts for her International Relations class.

“It’s because a woman leader has been democratically elected for the first time in 5000 years of Chinese history,” she told them the next day. However, some students did not take the treat well. “There was a comment later on in my evaluation about how I was biased towards the DPP,” says Ms. Sinclair. “I wasn’t thinking about the KMT or the DPP. I was thinking about the 5000 years of history.”

This event highlights the degree of sensitivity TAS students sometimes have towards mentioning current political issues in the classroom. Sometimes, students may construe even the act of bringing up politics as an indication of bias and conclude that their teacher has acted inappropriately.

“By their very nature, classroom spaces are political spaces,” says Mr. Walker, psychology and AP World History teacher. This means that it is impossible for teachers not to show their political loyalties whatsoever. Ms. Sinclair agrees that bias is unavoidable. She says, “I’m certain that despite my best intentions, I can find bias in almost every sentence I say, in the verbs that I choose to use.”

Distinguishing between making a connection to current events and advocating for a political view is difficult, especially when people have different opinions on where to draw the line.

Ms. Sinclair determines whether a political opinion is appropriate to bring up by considering how widely accepted the opinion is. “If it’s an ethical question, then I think it’s important to remain impartial.” She says, “I don’t see [expressing belief in the importance of human rights] as being a bias, or espousing my own political views, because that’s signed on by most countries.”

For Mr. Walker, expressing a controversial opinion is sometimes necessary, such as when talking about why genocides continue to occur around the world. “There’s always change you would like to see in the world, and part of it comes from having conversations with young people,” he says. “That’s where you are met with a dilemma. Do you embrace the standpoint where you shouldn’t be objective? Or do you try to temper what you’re saying? So I think sometimes you have to say it to some extent, even if you’re offering up a controversial viewpoint.”

Teachers face many challenges in accommodating everyone’s opinions on what constitutes the proper way to integrate current events into the curriculum while still showing how class topics are relevant to today’s world. However, the teachers agree that completely omitting political issues in an effort to remain objective would be a mistake.

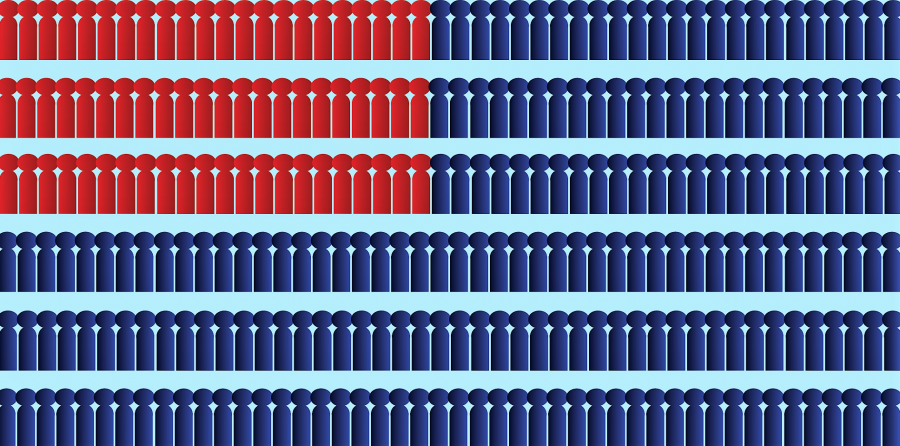

“When we’re doing ancient history, I’m thinking every class, ‘Why is this even relevant to what your future is?’ says Ms. Sinclair. “Civic engagement is the goal here. You want to have a well-informed populace.”

Mr. Walker agrees that students need to be taught how to reach informed opinions on political and social issues. He says, “It is important that students do learn to think for themselves, especially on very important topics. And the only way to do that is to welcome those topics into the classroom, to engage in those conversations.”

![A myriad of impressive trophies and awards. [ANNABELLE HSU/THE BLUE & GOLD]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Awards2-1200x512.jpeg)

![Students' calendars say goodbye to exam week. [ANNABELLE HSU/THE BLUE & GOLD]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Exam-week-1200x740.jpg)

![A collection of college flags. [PHOTO COURTESY OF AMBER HU ('27)]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_5029-1200x577.jpeg)

![An SAT word cloud. [PHOTO COURTESY OF WORDCLOUDS]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/SAT.jpeg)

![Collage of banned books, including “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood. [MINSUN KIM/ THE BLUE & GOLD]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IMG_4274-1200x681.jpeg)