Displacement: Exploring life between continents

As a child growing up in a small Taiwanese town, Dr. Daniel Long had never seen a McDonald’s, Starbucks, or even a 7-Eleven. The family television had three channels. So when he first set foot in America for college, the place he would eventually describe to others as “home,” it seemed like an alien planet.

“The difficulty for me was that because I was white, and I had an American accent, I was expected to fit in,” he says. “But I didn’t. For a long time, I didn’t have the social context that other people did. I didn’t know as much about sports teams. I didn’t have the same vocabulary.”

Throughout his adolescence, Dr. Long’s family held on tightly to vestiges of American culture. Every year, for example, during the Super Bowl, the family would wait to get the VHS tape that friends were sending from the U.S. in the mail. “We would watch it together two weeks after it had already happened,” says Dr. Long. “It was one of the only times I ever watched TV, because none of the three channels on television had English programming.”

of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

“No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese.”

Even though his family clung to these remnants of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

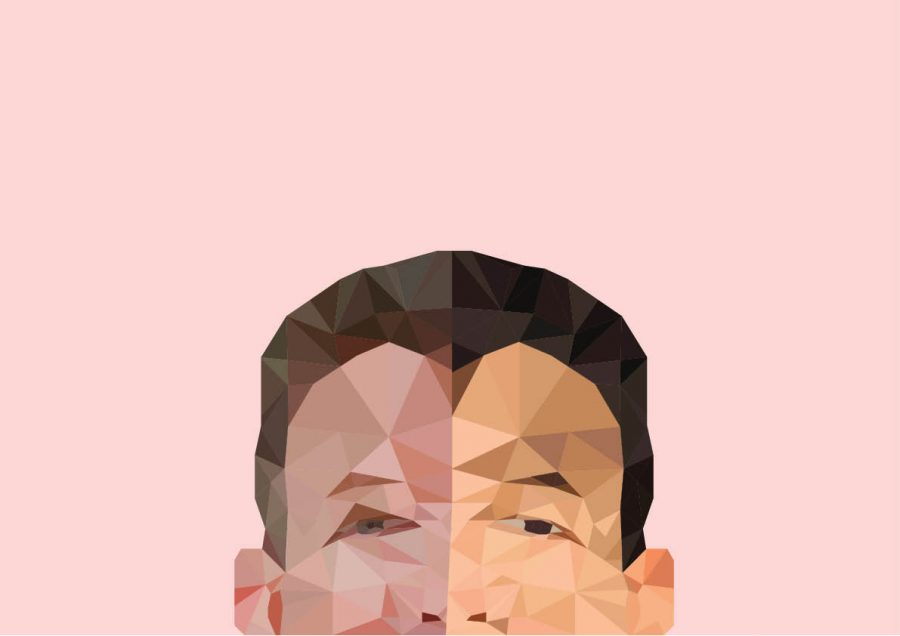

Meanwhile, his brother, Dave, embraced as much of America as he could from a continent away. “There was a striking difference between myself and my brother,” says Dr. Long. “My brother was adopted. Ethnically, he’s Korean. In everything else—the way he thinks, the way he behaves, the way he speaks—he’s very, very, American. He even joined the U.S. military. But people would still assume things about him because he didn’t ‘look American.’”

Dr. Long explains more about his childhood, his upbringing, and how he grew up.

In the same way that others had assumed that Dr. Long was fully American because of his appearance, Dave was often looked to as the bridge between Taiwanese individuals and the rest of Dr. Long’s Caucasian family. “People often turned to my brother to speak while we were in Taiwan, expecting him to translate and know more about how to communicate because he was Asian,” says Dr. Long. “No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese, while he never learned the language.”

What the brothers lacked in cultural commonalities, however, they made up for in their shared experiences as third culture kids who were constantly moving from country to country—first living in Japan, Vietnam, and Taiwan, before scattering across the world as they grew older. “As children, we got used to leaving people. We got used to moving on, pretty quickly,” says Dr. Long. “When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

“When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

Is it true? “Of course not,” he says. “It’s a coping mechanism. If I got upset and cried every time I had to go away, I’d be doing a lot of crying.” But he does admit that his childhood has instilled a wanderlust that was, at first, hard to shake. “It wasn’t until I met my wife, until I had kids and I grew roots in Taiwan, that I no longer felt the need to pack my suitcase,” he says.

At the same time, Dr. Long’s history has helped him create a new brand of friendship with fellow travelers. “I can move away and not see a friend for 20 years, then form an instant bond when we meet again,” he says. He also has an affinity with others who have been displaced often throughout their lives. “I gravitate to other third culture kids who can understand my experience, because I don’t have to explain,” he says. “I can tell them, ‘I’m from Taiwan,’ and they’ll understand.”

Where does he tell other people he is from? The closest approximation to a U.S. home is South Carolina, where his parents currently reside—but Dr. Long has only ever lived there for a year. The answer is not entirely inaccurate: He will always find a home “wherever Mom and Dad are,” he says. Large family gatherings occur every year in his parents’ Columbia house, where he reunites with his many America-dwelling relatives and his younger sister living in Tanzania. These meetings are what consolidates the emails, Skype calls, and Messenger chats that they use to try to maintain bonds within their family.

Still, Dr. Long’s voice is blase and a little resigned as he tells me of the barriers that keep him from claiming Taipei as his own. “The thing is, when people are asking me where I’m from, they’re not expecting for me to say Taiwan. So I say South Carolina. I lived in St. Louis for three years, so sometimes I say that too,” says Dr. Long. “The irony is that even though I know Taiwan much better than these other places, I’ll never be Taiwanese to the vast majority of people. It doesn’t matter how long I actually spend my life here. That’s just the cultural expectation, that to be from here you have to look a certain way.”

But then, his face clears. “Taiwan is a great place to be from,” he says. “It’s really a wonderful place, and I owe my parents for bringing me here. It’s been one of the great blessings of my life, even if I didn’t choose it.”

As a child growing up in a small Taiwanese town, Dr. Daniel Long had never seen a McDonald’s, Starbucks, or even a 7-Eleven. The family television had three channels. So when he first set foot in America for college, the place he would eventually describe to others as “home,” it seemed like an alien planet.

“The difficulty for me was that because I was white, and I had an American accent, I was expected to fit in,” he says. “But I didn’t. For a long time, I didn’t have the social context that other people did. I didn’t know as much about sports teams. I didn’t have the same vocabulary.”

Throughout his adolescence, Dr. Long’s family held on tightly to vestiges of American culture. Every year, for example, during the Super Bowl, the family would wait to get the VHS tape that friends were sending from the U.S. in the mail. “We would watch it together two weeks after it had already happened,” says Dr. Long. “It was one of the only times I ever watched TV, because none of the three channels on television had English programming.”

of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

“No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese.”

Even though his family clung to these remnants of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

Meanwhile, his brother, Dave, embraced as much of America as he could from a continent away. “There was a striking difference between myself and my brother,” says Dr. Long. “My brother was adopted. Ethnically, he’s Korean. In everything else—the way he thinks, the way he behaves, the way he speaks—he’s very, very, American. He even joined the U.S. military. But people would still assume things about him because he didn’t ‘look American.’”

Dr. Long explains more about his childhood, his upbringing, and how he grew up.

In the same way that others had assumed that Dr. Long was fully American because of his appearance, Dave was often looked to as the bridge between Taiwanese individuals and the rest of Dr. Long’s Caucasian family. “People often turned to my brother to speak while we were in Taiwan, expecting him to translate and know more about how to communicate because he was Asian,” says Dr. Long. “No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese, while he never learned the language.”

What the brothers lacked in cultural commonalities, however, they made up for in their shared experiences as third culture kids who were constantly moving from country to country—first living in Japan, Vietnam, and Taiwan, before scattering across the world as they grew older. “As children, we got used to leaving people. We got used to moving on, pretty quickly,” says Dr. Long. “When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

“When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

Is it true? “Of course not,” he says. “It’s a coping mechanism. If I got upset and cried every time I had to go away, I’d be doing a lot of crying.” But he does admit that his childhood has instilled a wanderlust that was, at first, hard to shake. “It wasn’t until I met my wife, until I had kids and I grew roots in Taiwan, that I no longer felt the need to pack my suitcase,” he says.

At the same time, Dr. Long’s history has helped him create a new brand of friendship with fellow travelers. “I can move away and not see a friend for 20 years, then form an instant bond when we meet again,” he says. He also has an affinity with others who have been displaced often throughout their lives. “I gravitate to other third culture kids who can understand my experience, because I don’t have to explain,” he says. “I can tell them, ‘I’m from Taiwan,’ and they’ll understand.”

Where does he tell other people he is from? The closest approximation to a U.S. home is South Carolina, where his parents currently reside—but Dr. Long has only ever lived there for a year. The answer is not entirely inaccurate: He will always find a home “wherever Mom and Dad are,” he says. Large family gatherings occur every year in his parents’ Columbia house, where he reunites with his many America-dwelling relatives and his younger sister living in Tanzania. These meetings are what consolidates the emails, Skype calls, and Messenger chats that they use to try to maintain bonds within their family.

Still, Dr. Long’s voice is blase and a little resigned as he tells me of the barriers that keep him from claiming Taipei as his own. “The thing is, when people are asking me where I’m from, they’re not expecting for me to say Taiwan. So I say South Carolina. I lived in St. Louis for three years, so sometimes I say that too,” says Dr. Long. “The irony is that even though I know Taiwan much better than these other places, I’ll never be Taiwanese to the vast majority of people. It doesn’t matter how long I actually spend my life here. That’s just the cultural expectation, that to be from here you have to look a certain way.”

But then, his face clears. “Taiwan is a great place to be from,” he says. “It’s really a wonderful place, and I owe my parents for bringing me here. It’s been one of the great blessings of my life, even if I didn’t choose it.”

As a child growing up in a small Taiwanese town, Dr. Daniel Long had never seen a McDonald’s, Starbucks, or even a 7-Eleven. The family television had three channels. So when he first set foot in America for college, the place he would eventually describe to others as “home,” it seemed like an alien planet.

“The difficulty for me was that because I was white, and I had an American accent, I was expected to fit in,” he says. “But I didn’t. For a long time, I didn’t have the social context that other people did. I didn’t know as much about sports teams. I didn’t have the same vocabulary.”

Throughout his adolescence, Dr. Long’s family held on tightly to vestiges of American culture. Every year, for example, during the Super Bowl, the family would wait to get the VHS tape that friends were sending from the U.S. in the mail. “We would watch it together two weeks after it had already happened,” says Dr. Long. “It was one of the only times I ever watched TV, because none of the three channels on television had English programming.”

of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

“No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese.”

Even though his family clung to these remnants of the American experience, Dr. Long usually spent much of his time immersed in a more Taiwanese mindset, forming his closest bonds with aboriginal children in town rather than hanging out with the small group of other western kids at the school he attended a 10-minute bike ride away.

Meanwhile, his brother, Dave, embraced as much of America as he could from a continent away. “There was a striking difference between myself and my brother,” says Dr. Long. “My brother was adopted. Ethnically, he’s Korean. In everything else—the way he thinks, the way he behaves, the way he speaks—he’s very, very, American. He even joined the U.S. military. But people would still assume things about him because he didn’t ‘look American.’”

Dr. Long explains more about his childhood, his upbringing, and how he grew up.

In the same way that others had assumed that Dr. Long was fully American because of his appearance, Dave was often looked to as the bridge between Taiwanese individuals and the rest of Dr. Long’s Caucasian family. “People often turned to my brother to speak while we were in Taiwan, expecting him to translate and know more about how to communicate because he was Asian,” says Dr. Long. “No one would realize that I was the one who spoke fluent Chinese, while he never learned the language.”

What the brothers lacked in cultural commonalities, however, they made up for in their shared experiences as third culture kids who were constantly moving from country to country—first living in Japan, Vietnam, and Taiwan, before scattering across the world as they grew older. “As children, we got used to leaving people. We got used to moving on, pretty quickly,” says Dr. Long. “When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

“When you’re a third culture kid, people think you’re flippant. They think you don’t care, when you leave because you just move on and adapt.”

Is it true? “Of course not,” he says. “It’s a coping mechanism. If I got upset and cried every time I had to go away, I’d be doing a lot of crying.” But he does admit that his childhood has instilled a wanderlust that was, at first, hard to shake. “It wasn’t until I met my wife, until I had kids and I grew roots in Taiwan, that I no longer felt the need to pack my suitcase,” he says.

At the same time, Dr. Long’s history has helped him create a new brand of friendship with fellow travelers. “I can move away and not see a friend for 20 years, then form an instant bond when we meet again,” he says. He also has an affinity with others who have been displaced often throughout their lives. “I gravitate to other third culture kids who can understand my experience, because I don’t have to explain,” he says. “I can tell them, ‘I’m from Taiwan,’ and they’ll understand.”

Where does he tell other people he is from? The closest approximation to a U.S. home is South Carolina, where his parents currently reside—but Dr. Long has only ever lived there for a year. The answer is not entirely inaccurate: He will always find a home “wherever Mom and Dad are,” he says. Large family gatherings occur every year in his parents’ Columbia house, where he reunites with his many America-dwelling relatives and his younger sister living in Tanzania. These meetings are what consolidates the emails, Skype calls, and Messenger chats that they use to try to maintain bonds within their family.

Still, Dr. Long’s voice is blase and a little resigned as he tells me of the barriers that keep him from claiming Taipei as his own. “The thing is, when people are asking me where I’m from, they’re not expecting for me to say Taiwan. So I say South Carolina. I lived in St. Louis for three years, so sometimes I say that too,” says Dr. Long. “The irony is that even though I know Taiwan much better than these other places, I’ll never be Taiwanese to the vast majority of people. It doesn’t matter how long I actually spend my life here. That’s just the cultural expectation, that to be from here you have to look a certain way.”

But then, his face clears. “Taiwan is a great place to be from,” he says. “It’s really a wonderful place, and I owe my parents for bringing me here. It’s been one of the great blessings of my life, even if I didn’t choose it.”

![Sofia Valadao [Erin Wu/The Blue&Gold]

Erin Wu [Annabelle Hsu/The Blue&Gold]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/erin-sofia-pic-600x450.png)

![Dr. Simeondis, Mr. Anderson. [Annabelle Hsu/The Blue&Gold]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/teachers-600x338.jpg)

![[PHOTO COURTESY OF UNCULTURED, JUNIPER AND CO.]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/student-businesses-600x338.png)

![Photo of the girl's varsity badminton team [PHOTO COURTESY OF TAS ATHLETICS]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/BadmintonTeam-04839-600x338.jpg)

![The Institute for Speech and Debate, now based all across the east coast of the US. [PHOTO COURTESY OF MR. WILLIAMS]

Mr. Morris' various ceramic artwork. [PHOTO COURTESY OF MR. MORRIS]](https://blueandgoldonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Untitled-design-1-600x459.png)